The timber industry is a cornerstone of Grays Harbor County’s economy and an important part of its history. Over 300 logging firms have operated in the county since the arrival of American settlers. One of the largest of these companies was the Polson Logging Company. A leader in the industry, at one point it controlled two sawmills, a shingle mill, 12 logging and construction camps and 100 miles of logging railroad.

The Polson Company was founded by brothers Alexander and Robert Polson, immigrants from Truro, Nova Scotia. The two brothers left the family farm for the American West. Alexander worked as a miner, cattle rancher and logger in South Dakota, Nevada, New Mexico, Arizona and California before coming to Washington. He was employed by Amos Brown as a timber feller near Olympia before moving to Hoquiam in 1882. Alexander went into real estate and timber. In 1891 he and his brother Robert—who arrived in Hoquiam in 1887—consolidated their timber interests into the Polson Brothers Logging Company. In 1903 the business changed its name to the Polson Logging Company, after affiliating with the Merrill & Ring Company.

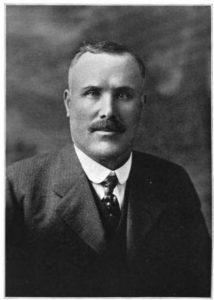

Alexander served as president of the Polson Logging Company while his brother Robert was manager. The brothers made a fortune through their logging company and expanded their business interests into other local timber companies. They even invested in mining in British Columbia. Alexander became a leader in Hoquiam and was elected to the state senate, an office he held for many years.

Their business boomed, becoming the leading timber company in Grays Harbor County. During this time Hoquiam, where the company was headquartered, steadily grew in population, increasing from 1,500 people in 1890 to 10,000 in 1920.

Most of the loggers who worked for Polson, however, did not live in town and only came in on paydays. They lived in temporary logging camps near where they worked. Bunkhouses, cookhouses, and other buildings were built on supports so that a camp could easily be moved by rail to the next logging site after the old one was logged out.

Polson workers came from all across the world. Many of them were Scandinavian, hailing from Sweden, Norway and especially Finland. In later years a number of them brought their families to live with them in the logging camps, turning these camps into small communities.

Logging was difficult, dangerous work and Polson was caught up in labor unrest. Alexander Polson, in the state senate, was a major proponent of anti-IWW legislation. His company remained a major employer in the region. It could brag in December 1914 to the Aberdeen Herald newspaper that it had an $80,000 payroll just as they closed for the Christmas holidays.

With a large area of operations, transporting logs was a major issue. Polson started out using ox-teams, but later switched to trains—first steam and later diesel. So important were trains to the group that one of their camps was even nicknamed “Railroad Camp,” where much of their equipment was stored and maintained. It took many skilled workers to keep the logging trains running. Later trucks became crucial for transportation.

While logs were often carried overland, they were sometimes transported by water, especially in the early years. The Polson Company gave its name to Polson Creek. Flowing out of their log dump at New London, the company floated logs down the creek using a series of splash dams. New London was even nicknamed “Log City.” The logs’ destination were the sawmills in Hoquiam.

Timber production in the Pacific Northwest peaked in the 1920s, so much so that historian Ed Van Syckel even titled his book “They Tried to Cut it All.” Instead, overproduction and declining demand led to a recession. Timber interests like Polson tried to adapt by starting pulp, paper and plywood mills. Problems worsened with the Great Depression, which declined global demand even further. In 1932 only one-fifth of all Hoquiam lumber industry was operating and 50 percent of those lucky enough to still have a job were working only part-time.

In the late 1940s Polson was sold to Rayonier Inc. This company continues to operate in Grays Harbor County today. The legacy of logging remains strong in the area. Many people and their family members have worked in the past for logging companies like Polson and Rayonier—or do so today.

People can learn more about the Polsons, logging and Hoquiam history at the Polson Museum at 1611 Riverside Avenue. The museum is housed in the home of Arnold Polson, built in 1924 as a wedding present from his bachelor uncle Robert Polson. This historic building was donated to the city of Hoquiam by his widow in 1976 and was made into a museum.